The history of English gives us reasons to embrace evolving language as we approach the new year.

“O, call back yesterday, bid time return”1

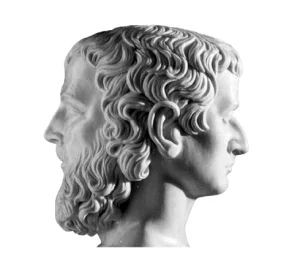

The winter solstice ushers in a transitional period. This is the time to think about the changes we want to make in the new year. Most of us plan to eat better, exercise more, make time to read, learn a new skill. But the approaching new year is also a time to reflect on past changes that brought us to this point in our lives. After all, January is named after the Roman god Janus. He’s the god of beginnings and endings; transitions; and gates, doorways, and passages. In art, he traditionally has two faces, one facing forward and one facing backward. One is often youthful and the other aged.

I started thinking about the English language from this dual perspective of Janus. Looking back, historical events forged English as we know it. Looking ahead, current events and popular usage will propel it forward. If the English language could be characterized by a single word, it would be change.

“What’s past is prologue”2

Waves of historical invasions carried new linguistic influences to England, starting as early as the sixth century BCE. The Celts brought the languages that would evolve into Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. The Romans brought Latin. After the Romans withdrew from England, the Germanic tribes moved in. These languages influenced the development of the language commonly known as Old English. The Norman Conquest of 1066 brought Norman French to England. This influenced Middle English, the country’s dominant language from around 1150. Modern English emerged around 1500. Countless historical events and linguistic influences altered the language, and scores of localized dialects emerged in the intervening years. Without this steady stream of new influences, the English language as we know it would not exist.

Language is still evolving in new directions almost faster than we can keep up. Editors and writers need to adapt to changes as they unfold in real time. This can be tricky, but I’ve learned to love the process because language is meant to evolve. Wouldn’t the world be a little less colorful if language remained static? Imagine what English might sound like if it was harnessed to early medieval Saxon ideas. Weird, right? There’s a reason why “wordies” (a term from 1982) get excited about updates to the Oxford English Dictionary. (“Influencer” and “side hustle” made the cut this year.) We’re seeing language evolve in real time, and it can be thrilling.

“Old fashions please me best; I am not so nice / To change true rules for odd inventions”3

Linguistic change can be cringey (another word from the 1980s). Here’s an example. Growing up, I understood that “waiting for” something was correct unless a server was “waiting on” a customer. Then I heard John Mayer’s song “Waiting on the World to Change” (released in 2006), and my world turned upside down. It felt wrong. Every time I heard it on the radio I wanted to shriek, “Waiting for! It’s supposed to be waiting for!” I don’t know whether John Mayer is responsible for popularizing this usage or not. But somehow, it has become far more common to hear “waiting on.”

Over time, I’ve accepted this as the new normal. I appreciate the fact that common usage drives the evolution of language. Scholars estimate that William Shakespeare introduced about 1,700 new words into English. There must have been people who resisted this change the way I resisted John Mayer’s. But without Shakespeare, we wouldn’t have “gloomy” or “gnarled”—or knock-knock jokes. In the end, the gains are greater than the losses.

As we look ahead to the new year and reflect on the old, my argument is this: If we don’t learn to live with change, we trivialize the forking paths that gave us modern English in the first place. New influences will forge the next stage of the language’s development. We don’t have to wait for the world to change—we are driving the change.

1 William Shakespeare, “The Life and Death of King Richard the Second,” Act III, Scene II.

2 William Shakespeare, “The Tempest,” Act II, Scene I.

3 William Shakespeare, “The Taming of the Shrew,” Act III, Scene I.